If photography had been the bi-product of a project to unravel the secrets of time travel we might have used the name “time machine” instead of “camera”. Sure, a photograph doesn’t enable you to travel back in time but a good one sparks the imagination, the dead look through you with living eyes. So it wouldn’t be so weird to call image capturing technology “time machines”; just inaccurate, confusing and cruel, suggesting them to be the thing they feel like rather than what they are.

When not yet inventing Artificial Intelligence more could have been done to popularise the more accurate name Large Language Model. Instead we renamed the thing we hadn’t done. Time travel would have had to become General Time Travel, the way AI is now AGI. Turns out the Turing Test is easy to pass once you game the human element and play to our love of hyperbole and willingness to buy into illusion. What we now call AI is many things but it is only intelligent in the way a photograph transports us in time, the magic is still in our heads.

Nevertheless, crawling into the candlelight end of one of the hardest years in the film and tv industry, muttering to ourselves the current mantra “survive ’til 25”, it’s not surprising that a lot of writers are pessimistic about the impact of pretend AI on creative jobs. Dispense with the misplaced mysticism, LLMs are still a huge development. They are not electronic minds buzzing with original thought but it’s no small matter to swiftly interrogate a vast history of written stories and from that predict other things that will also feel like stories. LLMs are “Save The Cat” on an inconceivable scale.

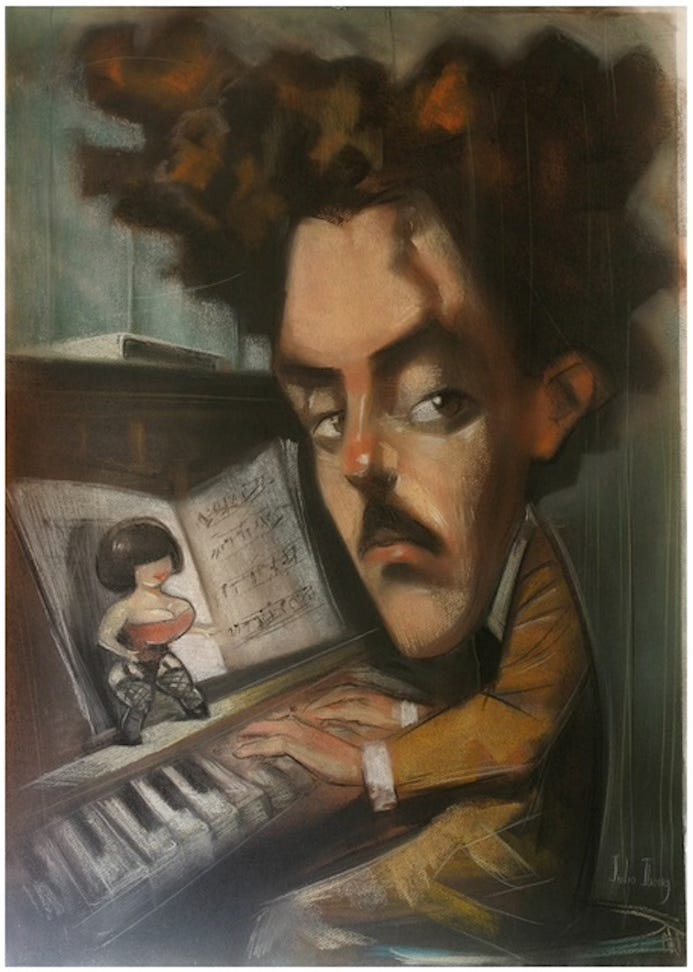

A long time ago I met a dancer who wanted to collaborate with me on an adaptation of a short story by the magic realist author Felisberto Hernández. She wanted to work with someone because her training as a dancer, which had taught her body to instinctively respond within the physical grammar of a creative tradition, had made her better at dancing but forever divided her from that original, urgent, joyful movement that came out of her as a child. Having learnt how to dance properly she could never again do it with innocence. She didn’t want to do to her writing what she had done to her dancing.

I understood her reticence. It has always felt to me joyless to learn about storytelling by following the heroes path already trodden by the likes of Joseph Campbell, Christopher Vogler, Robert McKee, Syd Field, John Truby and yes dear old Blake Snyder whose rules of screenwriting include the specific page number where certain events should land.

“Page 25 is the place where I always go to first in a screenplay someone handed me (we all have our reading quirks) to see “what happens on 25.” I want to know I) if anything happens and 2) if this screenwriter knows that something should happen. And I mean something big…”

If the 21st Century were a screenplay then Blake would also have next year in his sights, survive to 25, or beyond it, and perhaps this story is about you after all...

Traditional screenwriting bibles attempt to show how to recreate what has already worked. They are Small Language Models. Artificial Illusory Intelligence isn’t a new idea, it’s an incredible implementation of an old one. It draws on vastly more data and does so at astonishing speed but retains the same inevitable drawbacks. Modelling your work around what has already been made inevitably squeezes out some of the you-ness that makes it unique.

Does this make it the end of our profession, our industry, our culture? Or just another tool, not be feared but mastered? Certainly my personal hell instagram feed is suddenly full of (oddly muscular) dudes gruffly offering “The 4 AI prompts you need to ensure Netflix will buy your story”. It’s not quite “Get your story ripped and beach ready in just three weeks” but it still smells like bodybuilding snake oil for the mind.

In the hands and heads of humans tools are never just tools. Our entire history as a species is the story of using tools to make better tools to do even more appalling things to each other. Sure, guns don’t kill people, but they do make it much easier for people to kill people. Taking guns out of a population doesn’t stop all murders but at least it adds some grit into the system of mayhem and despair. Inconvenience a murderer and some will end up never being murderers at all.

How we understand the function of a tool also matters. Shields and kevlar jackets protect, the function of a gun is to injure. Not only are LLMs not truly intelligent but drawing their power from aggregating vast swathes of existing data, the real expressions of real minds, they’re not even truly artificial. How can we use this tool right if we can’t even name it? What then, a Speed Reader? An Auto Summariser? A Digester? A Suggester?

The truth behind the saying “for a boy with a hammer every problem is a nail” is that having learnt how to use a tool, the real skill is knowing when not to. The strength of LLMs is their speed, so to use them successfully you’ll need to look for ways to slow down your thinking, to put some grit back into your creative process.

My dancing partner was right to see that we can never go back to not knowing, but wrong to imagine the solution was to stay innocent. Even if we had a General Time Machine the point would be to send our experienced selves backwards; it would be less helpful if in returning to the past we once more became part of it, unaware even of our impossible privilege.

Dancing is a way of being but writing is acting without applause and acting is pretending to the point of reality. When we allow ourselves to interact with machines as if they were as alive and alert to us as we are to them, we are acting our innocence. Don’t imagine you can’t get the benefit of innocence by acting out your own first encounter with your work as you reread it for the hundredth time. Pretending you don’t know is still the most powerful magic we have.

My screenwriting class starts tomorrow but for once I still have spaces - fill them here.

Meanwhile my brilliant friend Julia is raising money for a short film that retells a true story of addiction and recovery through the lens of a wild compulsive affair. It’s rare for a script to be both hot and genuinely moving and doing both in ten minutes is quite a gift. Let her tell you all about it here…