Surfaces.

Why you should judge a book by its cover.

This might not be a problem you suffer from but I feel I’ve got too good at not judging a book by its cover.

It might be that my taste in books has improved. I have a very clear memory of standing in an over lit bookshop in the Hatfield Galleria browsing the sci-fi titles when my mum warned me not to judge a book by its cover. If I’d heard the expression before it had never registered in quite the way it did then; perhaps because the paperback edition of Isaac Asimov stories in my hand was a perfect example of a cover that promised robots and space battles and yet would turn out, as I later attempted to drag my eight year-old eyes across its dense pages, to mainly be about the bureaucratic problems of administering a human colony on Mars. The cover could only have been accurate had it been an image of a freshly decorated wall with a small notice reading “caution, paint drying”.

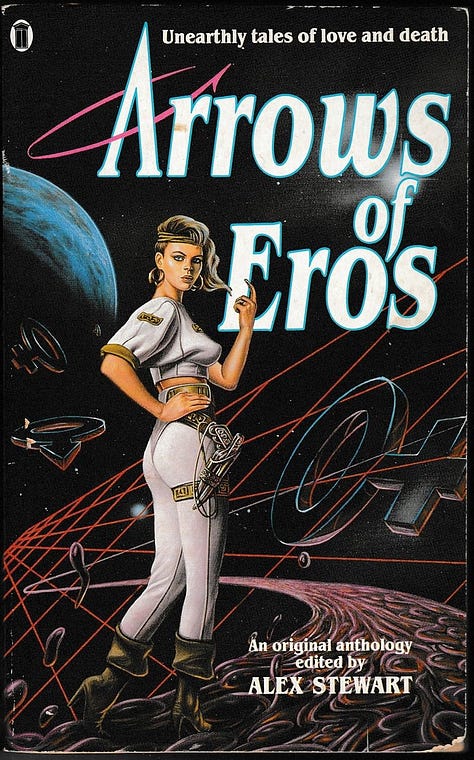

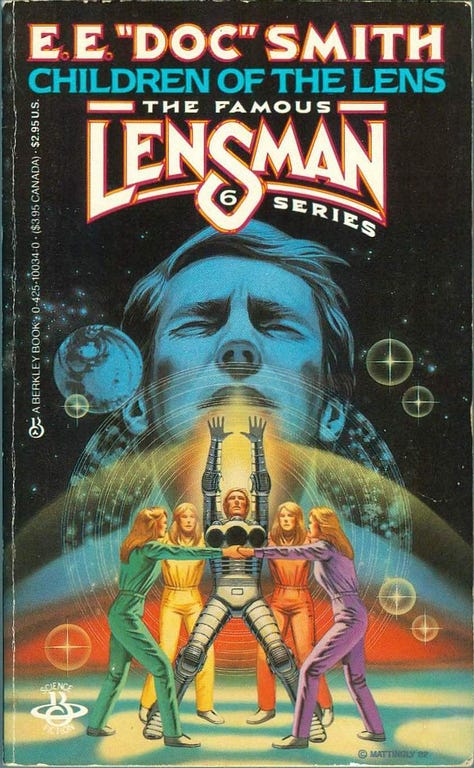

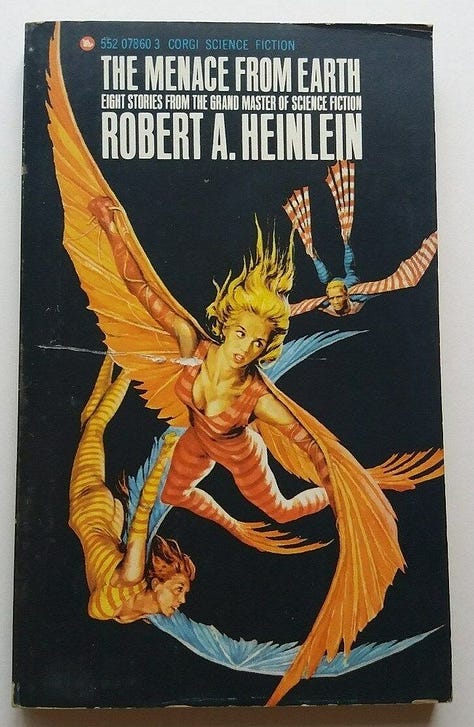

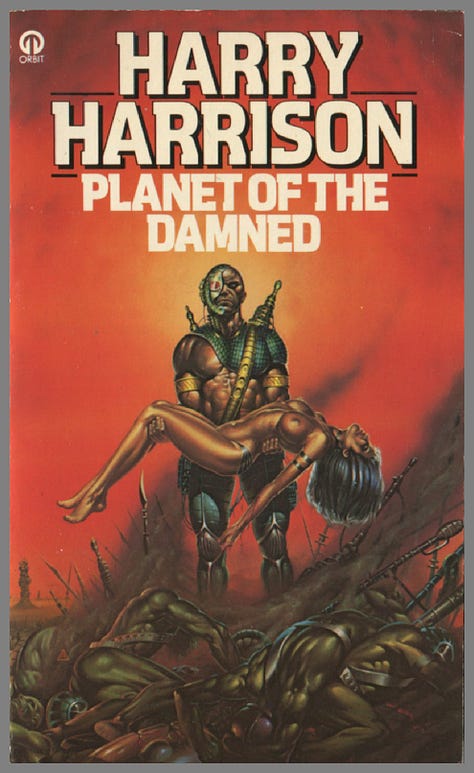

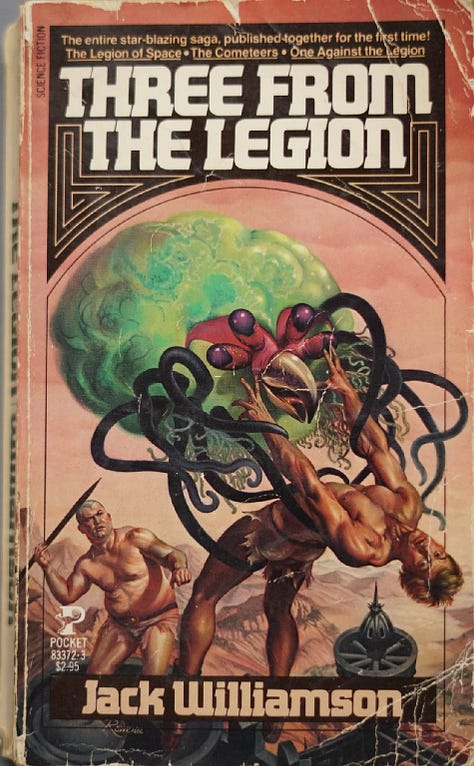

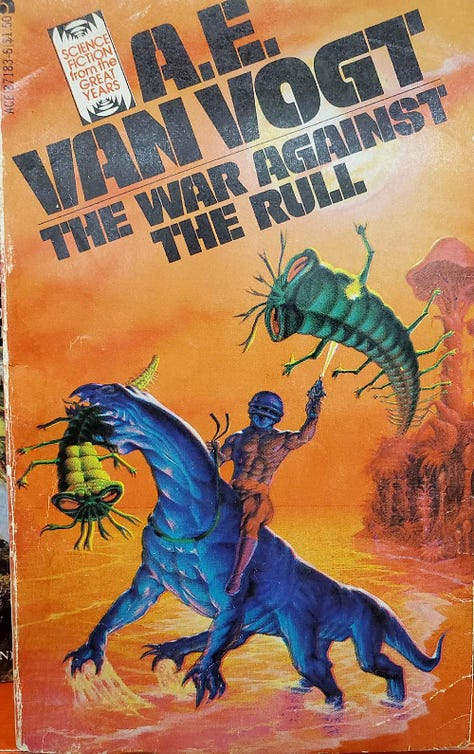

Growing up reading science fiction and fantasy the fear of miss selling always loomed. Would the monster really be that scary? Would the provocatively posed laser-gun toting space vixen actually feature as a character at all? Could the mesmerising illustration of the hero’s life and death struggle with a half-robot half-squid like enemy possibly be matched by the sparse, some might say, workmanlike prose that would inevitably fill the couple of hundred pages hiding within? Someone wanted my pocket money and I needed to learn to outsmart them.

To be fair the books of the late 1980s and early 1990s, the publisher’s over eager realisation of their author’s visions were nothing compared to what came at us from the nascent games industry. If you consider the man I am today as any sort of cynic then please compare the vivid box illustrations of early computer games to their actual 16-bit gameplay reality and you’ll understand that my youthful heart was wounded by some very deep betrayals. The worst of this was a book I got from the school library which promised to teach me to create my own computer games using Basic code.

The games were lovingly illustrated by graphic artists who clearly had been given no brief beyond the title and some money to spend on weed. One depicted a muscled warrior locked in deadly battle with a monstrous giant worm, its hideous mandibles open wide to devour him. I raced to type out the nearly 60 lines of nonsense that apparently would transform my home PC into some kind of temporal vortex through which my soul would travel into the thrilling netherworld that was the lair of this deadly Wyrm. But some hours later I discovered all that would happen was a pair of large OO’s would slowly and silently move across the screen until they eventually ate my cursor. This might explain why at times I am tempted to regard the destruction AI art is bringing to the profession of graphic design as the reaping of a whirlwind bitterly sowed.

However whilst my literary tastes have since expanded, it is more important to note that both publishers and writers have now developed a far more acute understanding of their task. The short term buzz of taking “any old shit” and putting a hot girl and a robot on the cover is a con with the long term outcome of dissatisfied customers. Rather than trying to dupe us, the writers and sellers of books, of games, of films, have instead learnt to self-censor themselves into being addictively interesting. Of course you can judge a book by its cover - who these days would dream of writing something that didn’t inspire an eye-catching cover? In such a saturated market, who would ever choose to publish a story that didn’t capture its audience? In late capitalism no one will tell you what you can and can’t write, no bounds are placed upon an artist’s creative imagination, save for those of self-restraint. We create what we know the market wants us to.

However our relationship to marketing is now so advanced we struggle to accept anything at face value. The brash charm of 1950’s marketing - “buy this thing: it’s a good thing and cheap too!” - was soon superseded by the illusive appeal to the allure beyond the surface - “buy this thing: it’s the thing smart sexy people like you buy”. Even when advertising briefly returns to simplicity, like the famous Ronseal - “it does exactly what it says it on the tin” the appeal is as much the reassurance that you should buy this because you are the sort of sensible down-to-earth customer who doesn’t fall for marketing bullshit. That’s why the slogan became so popular in politics despite this being a sphere where few did exactly what they said and nothing was delivered in tins.

Increasingly the things themselves feel almost immaterial. Brands, once a guarantee of quality, are now an expression of personality. We see through surfaces and live in an almost spiritual state of perpetual symbolism. We buy things not to own them but to tell the world what sort of person we are. The same is true of our actions beyond our purchasing. Social media isn’t an arena for the sharing of ideas but the wearing of them. As we judge each other by the quality of our reposts “I think therefore I am” grows a strange new meaning - “I think this therefore I am that”.

This might seem like a whole new argument for not trusting covers. Isn’t virtue signalling just the same hypocrisy we have always known? At times perhaps, yet increasingly I think people, like authors, are rewriting themselves to fit the covers they have chosen. Social media inspires often surprising and usually swift moves across the political spectrum - doubts about vaccines turning into election denial, fears about military aggression turning into justifying terrorism. These are not just symptoms of how social media struggles with nuance. These are the acts of people desperate to close the gap on their own hypocrisy, to rewrite their stories to be in line with their cover image.

We have taught ourselves to never expect honesty but when someone tells you who they are it is often best to believe them. Who was surprised that Boris Johnson’s brief tenure as Prime Minister ended in a tumble of corruption and self-idolising scandal? Only those centrist parts of the Conservative Party who had managed to delude themselves that the weight of the job might change the man, that he was somehow not the corrupt narcissist he had always very openly been.

We live in an age where judging books by their covers is a powerful skill to hold onto. We have grown so accustomed to the tyrannical fear of hypocrisy, quick to cry foul on anything or anyone who is less than they claim. But men like Johnson and Trump are not hypocrites, they honestly are as bad as they seem. What is bad does not become good just because it is what we desire. Worse than trusting a hypocrite is reaching out for things, objects, people, actions, revenges, because we want them to be what we already know they are not.